Ukraine's gamers are helping target Russian units with their own code

Inside Ukraine’s very 2023 Bletchley Park: The Mail’s RICHARD PENDLEBURY is given unprecedented access to the scruffy Kyiv flat where two board-gaming pals have developed super-smart software that’s becoming Putin’s worst nightmare

- The band of gamers are now helping to target Russian units with their own code

- See Richard Pendlebury’s exclusive report on the Daily Mail’s YouTube channel

The female of the species is more deadly than the male, Rudyard Kipling suggested. In Ukraine, the exploits of a certain Griselda would seem to bear that out.

Last autumn, Griselda was in the vanguard when the Ukrainian army burst through Russian lines during the Kharkiv counter-offensive, winning back hundreds of settlements and more than 10,000 sq km of occupied territory.

She also played a crucial part in the tracking, targeting and elimination of at least three Russian army generals by long-range missile strikes.

Hundreds of ordinary Russian soldiers who had gathered in a barracks in occupied territory were killed or wounded in another successful operation in which Griselda participated.

But her superpowers can also be used to save lives. This summer Griselda helped rescue hundreds of civilians at risk of drowning or starvation following Russia’s destruction of the Kakhovka dam.

But who is Griselda? Or, rather, what is Griselda?

Griselda is the codename for an automated military data-intelligence system developed, and run, by a hand-picked group of Ukrainian civilians with computer gaming and other IT backgrounds.

Click here to see the exclusive full report on the Daily Mail’s YouTube channel.

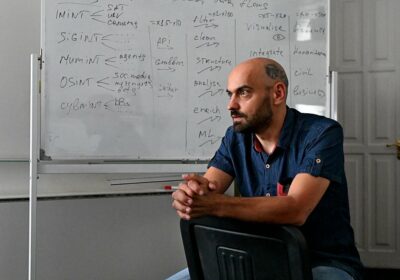

Fighting back: Richard Pendlebury (left) is shown how the Griselda system works by Oleksii Teplukhin

Before the invasion Griselda did not exist. It was set up in extremis, to assist Ukraine’s beleaguered armed forces strike faster, harder and further against the Russian invader.

The project’s co-founders, two forty-somethings called Oleksii Teplukhin and Dmytro Shamrai, first met 14 years ago through their love of fantasy-themed board games. Now Griselda allows them to play a daily game of life and death against the Russian military machine.

Mail cameraman Jamie Wiseman and I were recently allowed access to the Griselda HQ in Kyiv. We can now tell some of her remarkable story.

Perhaps the most celebrated example of academics, eggheads and other puzzle-solvers being brought together for a wartime intelligence mission occurred at Bletchley Park in England during World War II.

The Victorian mansion and estate in Buckinghamshire was then home to the Government Code and Cypher School. Their speciality was the interception and analysis of enemy communication traffic.

With the outbreak of war, Bletchley Park’s staff swelled from a few hundred to several thousand – mostly civilians – led by intellectual luminaries such as Alan Turing. They were able to crack the German codes, allowing the Allies to read Axis powers’ signals almost in real time.

To assist this work, the Bletchley Park codebreakers built Colossus, now regarded as the world’s first programmable, electronic, digital computer system.

The resulting intelligence arguably shortened the duration of the war.

The Griselda HQ in Kyiv is no Bletchley Park and Griselda herself is a very different creature from Colossus. But there is an undeniable historical, technical and motivational connection between Turing’s pioneers at Bletchley and the occupants of the rather scruffy top-floor suite that Griselda calls home.

Griselda’s co-founder Oleksii Teplukhin was part of that peacetime scene and ran his own IT company which was involved in a number of projects, including software development for a gambling firm. His partner Dmytro Shamrai was a well-known social activist

The open-plan apartment, with kitchen diner, is devoid of decoration and a little untidy, as one might expect of a place where IT guys hang out. The only clues as to what happens here are the open laptops, a whiteboard covered in programming notes in Ukrainian and the mantelpiece of the fireplace on which are displayed a deactivated rocket-propelled grenade warhead, a rocket launcher case, a gas mask and a bayonet.

There are only three people in the room. Two of them are wearing shorts, all are bearded and in stockinged feet.

The internet age allows Griselda’s software developers and operators – some 50 in total, both male and female, none older than 45 – to work remotely across Ukraine and in several other friendly countries.

Before the invasion Ukraine was already a centre of excellence for software development, particularly in the gaming sector.

Boosteroid, the largest independent cloud gaming provider in the world, has its development team based here. Last spring, tech leviathan Microsoft announced a ten-year agreement with Boosteroid to bring games such as Call Of Duty to the platform.

Griselda’s co-founder Oleksii Teplukhin was part of that peacetime scene and ran his own IT company which was involved in a number of projects, including software development for a gambling firm. His partner Dmytro Shamrai was a well-known social activist.

On the otherwise empty bookshelves of the Griselda HQ there is a stack of the kind of fantasy-themed board games – including Eldrich Horror and a version of Game Of Thrones – which brought the founders together.

I ask Teplukhin if he considers himself to be a geek. ‘I don’t think I’m a geek,’ he replies, defensively. ‘I ride a motorcycle, I ride a snowboard. I can’t call myself a geek but maybe others will think so.’

Shamrai, who is wearing a camouflaged bucket hat, explains: ‘It was in the first days of the invasion and we could hear the Russian artillery on the edge of Kyiv. To drown out that sound, we cranked up the gangsta rap we were listening to on our music player’

This scenario is analogous to the Ukrainian military’s struggle at the start of the invasion to collect, analyse and act upon the millions of pieces of intelligence data that were coming in from myriad different sources, every day

The question is a little unfair. Teplukhin’s skull is shaven and decorated with a large geometric tattoo. He helps target Russian forces for a living.

READ MORE: What the trench fighting of Ukraine war is really like: The inside story of RICHARD PENDLEBURY and JAMIE WISEMAN’S unprecedented access to the Ukrainian front lines, 400 yards from the Russians in scenes eerily reminiscent of WWI

Richard Pendlebury on patrol with Ukrainian Special Forces soldiers in front line trenches

He is most certainly not your average office IT guy.

In the first week of the invasion. Teplukhin packed his family off to Western Europe and joined the army to make what looked to be a last stand against overwhelming odds. But almost at once, he began to get requests from the embattled authorities to provide specialist IT help, not least by his board-gaming friend Dmytro Shamrai.

‘Dima worked in Kyiv city hall on different tasks and some of these tasks were related to IT, Starlink [the satellite broadband service], the internet and so on, and he asked me to join them,’ says Teplukhin. ‘When [it became clear] that Kyiv would not fall . . . and that I’m definitely not so useful as a serviceman, I agreed.’

Along with Shamrai, Teplukhin was put in charge of a small team that would grow into the Griselda project.

Very soon, they recognised what Teplukhin describes as a ‘huge problem’ undermining the effectiveness of Ukrainian military operations. From the start of the invasion, Ukraine was outmatched by Russia by every military metric, possessing only a fraction of the manpower, tanks, aircraft, artillery, air defence and electronic warfare capability that Putin’s army had at its disposal.

But there was another serious shortcoming. Imagine a 3,000-piece jigsaw puzzle being emptied onto a large table in front of you. You are told you must complete the puzzle not in days or weeks, but minutes or seconds.

And there is a further challenge. Some of the pieces you need are laid out on other tables in neighbouring rooms. But the doors to those rooms are locked and you don’t yet have the keys.

This scenario is analogous to the Ukrainian military’s struggle at the start of the invasion to collect, analyse and act upon the millions of pieces of intelligence data that were coming in from myriad different sources, every day.

Such information was being stored by a number of computer programs that were not integrated, or with different departments or formations in the field that had no means of sharing the knowledge. Sometimes vital intelligence was not used at all.

Similarly, analysis of battlefield situations was being carried out by servicemen sorting documents manually and using office spreadsheet-style technology.

Such work might take days to come to a useful conclusion, by which time the tactical requirements could well have changed.

Ukraine did not have that time to spare. And so the civilian super-techies were called in. Codename Griselda began to take shape.

‘It evolved very quickly, because we worked mostly 24 hours a day,’ says Teplukhin. ‘That’s all we did, except sleep and eat.’

But why did they decide to call their project Griselda?

Shamrai, who is wearing a camouflaged bucket hat, explains: ‘It was in the first days of the invasion and we could hear the Russian artillery on the edge of Kyiv. To drown out that sound, we cranked up the gangsta rap we were listening to on our music player.

‘At that moment the question of what to call our new project was asked and we looked at the music player and saw the rap was by a group called Griselda. So that’s how we came up with the name.’

Within a few weeks of this fraught conception, Griselda was born.

Griselda is the codename for an automated military data-intelligence system developed, and run, by a hand-picked group of Ukrainian civilians with computer gaming and other IT backgrounds

Teplukhin uses his whiteboard to explain how she works. The first stage of the process is the collation of all available intelligence. The sources can be broken down into five distinct categories.

IMINT stands for Imagery intelligence and includes pictorial data collected by satellites, drones, or cameras of any kind.

SIGINT or Signals Intelligence, the Bletchley Park speciality, comes from all kinds of enemy communication interception.

HUMINT or Human Intelligence is data provided by men or women on either side of the frontlines, including secret agents and civilians in occupied territory.

OSINT, or ‘Open Source Intelligence’, is data collected from social media and websites.

CYBERINT is the results of penetration of enemy databases.

On its own, each source is useful, but can be one-dimensional.

The Griselda platform automatically processes and integrates all the available data to provide the most accurate three-dimensional picture of what is happening on the ground at a given location.

Teplukhin gives an example of how this could play out.

A Ukrainian grandmother is living in a village in territory occupied by the Russian military. A Russian rocket launcher vehicle enters her village and is seen by Granny.

Using an encrypted messaging app on her mobile phone – most Ukrainians have these installed – she relays her sighting and the location to her son on the other side of the frontline. He in turn passes on the information to the Ukrainian military.

The project’s co-founders first met 14 years ago through their love of fantasy-themed board games. Now Griselda allows them to play a daily game of life and death against the Russian military machine.

A Griselda operator is now tasked to analyse Granny’s report, and does so by drawing on all the latest intelligence information held on the platform for that village and the surrounding area. The operator looks at satellite images, footage from drones and indiscreet chatter on a Russian Telegram channel used by its frontline soldiers.

READ MORE: Ukrainian geeks who went to war: The unlikely band of videogamers who run top secret ‘Griselda’ unit linked to the death of three Russian generals and targeted hundreds of soldiers

This done, the operator assesses Granny’s report as being ‘highly credible’ and passes his analysis, including a Griselda ‘visualisation’ of the target location, back to the military. As a result, a suicide drone is launched from the Ukrainian frontline. It finds the rocket launcher at the edge of Granny’s village and destroys it.

The average time for a Griselda operator to be given such a ‘task’, type in the coordinates and produce their report or ‘ticket’, is only 27 seconds, the Griselda team claims. That is the time it takes Griselda to complete that 3,000-piece jigsaw.

Ukrainian battlefield units can access the Griselda matrix using logins and passwords. Unsurprisingly, the Russians have tried to do the same.

‘We faced cyber-attacks from the second month of our existence,’ says Teplukhin. ‘At that time, no one [was supposed to] know about Griselda, but the Russians knew and tried to attack us, [though] unsuccessfully. They are not stupid guys.’

The 2022 Kharkiv counteroffensive, Ukraine’s biggest battlefield success to date, was the first time Griselda was used in a large scale, fast-moving operation.

‘Every few hours our ‘customers’ from military squads asked us to send them information about the next territory . . . the next ten kilometres, the next ten kilometres, the next ten kilometres . . . And [so the advance] continued,’ says Teplukhin.

He is less forthcoming about more specific targeting operations, such as those against very senior Russian officers.

According to the Ukrainians, 15 enemy generals and one admiralhave been killed since the invasion. Griselda was involved in several of these strikes, we have been told by defence sources.

‘I’m sorry, I cannot tell you details about our military operations,’ says Teplukhin when asked to confirm this. He also declines to comment on Griselda’s role in a missile strike on a barracks housing several hundred Russian troops, saying, ‘that’s too sensitive’.

But Griselda doesn’t just help wreak havoc. She has assisted in a number of humanitarian operations. When in June the Russians blew up the Kakhovka dam on the Dnieper river, some 600 sq km of land was flooded and tens of thousands of civilians were caught up in the aftermath.

The breach was unexpected and, at first, rescue attempts were disjointed and haphazard.

‘Volunteers from Kherson asked us to create a [data processing] system, to save people who were stuck in first floors of buildings in flood territory,’ Teplukhin explains. ‘It was extremely urgent because many of these people were [facing] not their last days, but their last hours.’

Within ten hours, the team had created an app they call ‘Griselda Evacuation’. This collated all the rescue requests that were being put out on social media and other platforms, weeded out those that were already resolved or fake, then prioritised those that were not.

‘Because, to save a dog is important, but to save 25 old ladies and men who are stuck on the first floor in their building is much more important than the dog,’ Teplukhin says. ‘Our app was involved in more than 800 rescues.’

Teplukhin says it shows how Griselda can be put to any number of complex tasks, far beyond war-fighting. The volunteer team is now looking for investors and partners ‘from friendly countries’ in order to expand.

In turns deadly and beneficent, Griselda will live on, well beyond the war that created her.

Source: Read Full Article